Here before us are three figures, finely potted with separate arms and whips. They are beautifully decorated with fine detail – quite a lot of time must have been allowed for the painters and a good range of enamel colours has been used as well as touches of gold both on the equestrian costume and the base line. They are not titled.

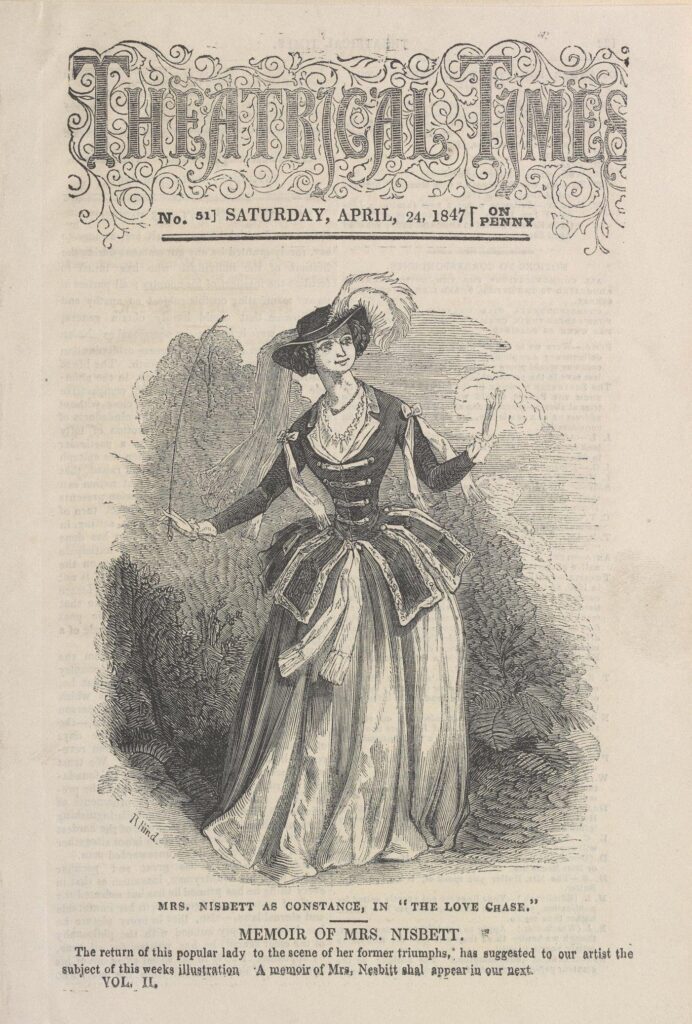

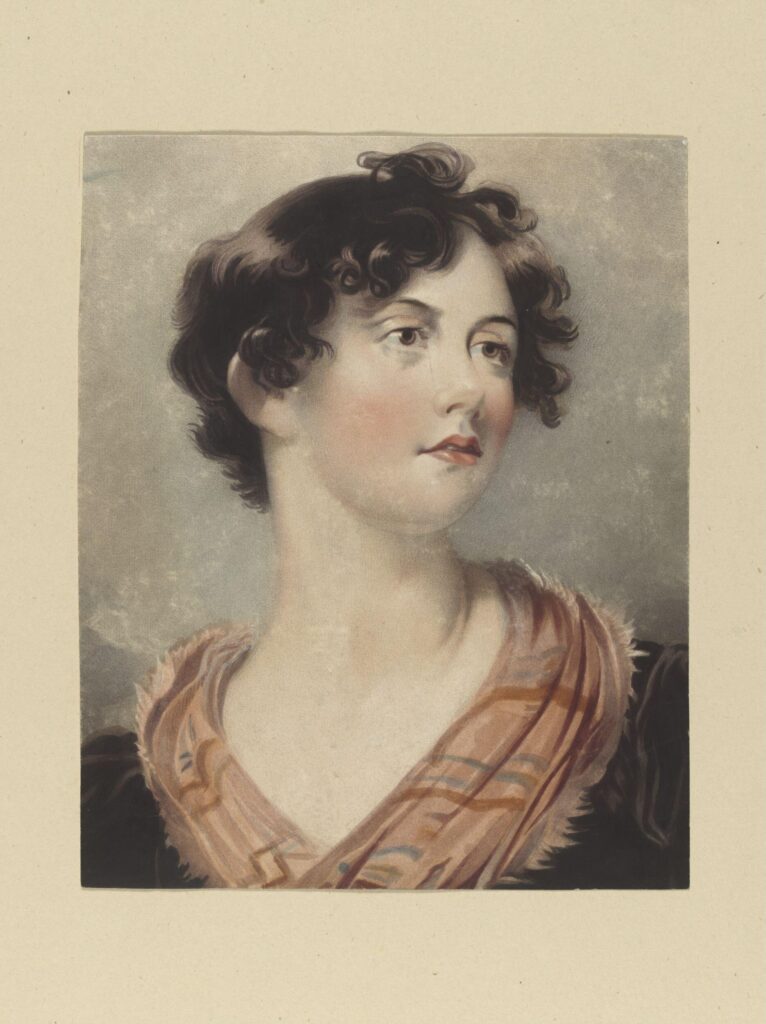

Our first candidate is Louisa Cranstoun Nisbett (1812 – 1858), an accomplished comic actress who starred in many stage shows. Her theatrical name was Miss Mordaunt, but she was also known as Miss Macnamara (her maiden name), Louisa Cranstown Macnamara and Louisa Crantoun. Later she became Lady William Boothby. She was considered a beauty, with an hourglass figure, eyes that sparkled, glossy dark hair and a musical laugh.

In 1837 a 25 year old Louisa Nisbett appeared as Constance in the premiere of “The Love Chase”, at London’s Haymarket Theatre. This play in five acts by James Sheridan Knowles (1784 -1862) was the “rom-com” of its day, with its crossed-wires plot and happily-ever-after ending of three weddings. Other actresses including Miss Elphinstone played this part over the years, but Constance would forever be tied to Louisa Nisbett, as her greatest dramatic success.

You can see from the illustrations that the character of Constance was depicted wearing a plumed hat and whip, as with the three figures we are examining. Louisa Nisbett was very well liked by theatre-goers and a good candidate for the Staffordshire potters to model – she was so famous that ten years after the premiere of “The Love Chase” her memoirs were published in The Theatrical Times with an illustration of her as Constance on the front cover. In fact, there is a figure always referred to as “Nisbett”, which closely resembles that 1847 image, but it is not as finely modelled or decorated as the three figures we are looking at.

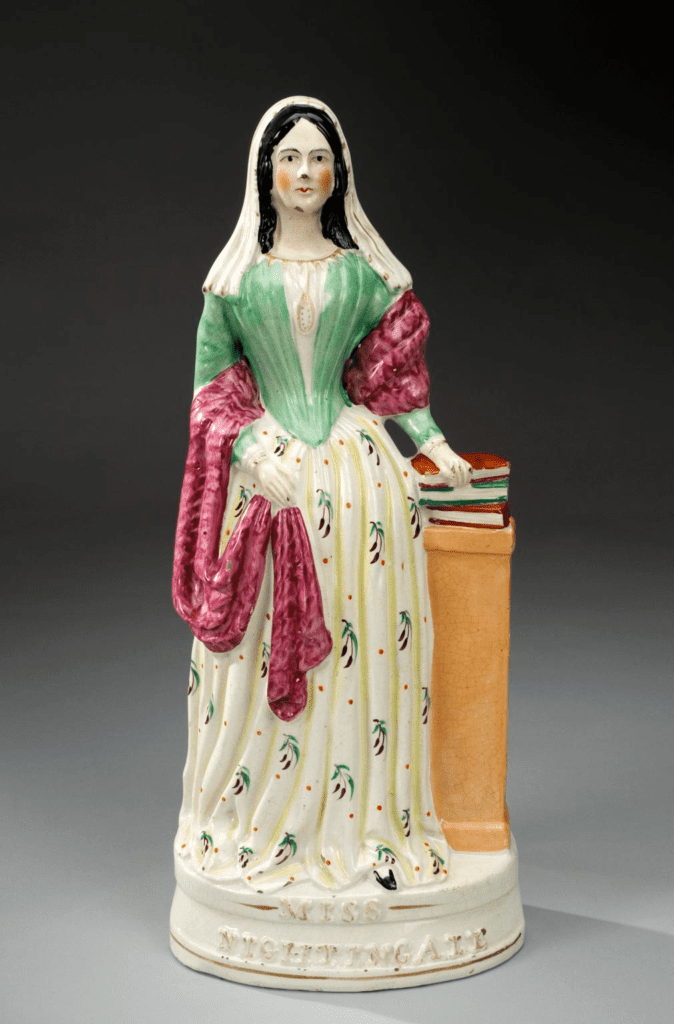

Let us then rule out Louisa Nisbett as Constance for our figures. Still, the potters clearly wished to depict a woman with an immediate and arresting dynamism – they have a presence about them which is not often found in female Staffordshire figures. Next to these three, the figures of Queen Victoria, other Royals or even Florence Nightingale, seem quite static and “flat”. Compare them to the figures of Jenny Lind, both as a theatrical character and as herself. These were also based on engravings of the time and depict her quite demurely. The Jenny Lind figures have little of the impact of this bold, vivacious woman.

Apart from the differences in the enamelling of the costume the same colours seem to have been used across all three figures – just applied in a different way. One interesting change in the centre figure is that the cravat (not a simple scarf as in the other two versions) has a small bow impressed into it at the front instead of the collar of the blouse. All of the figures share a unifying pattern: tartan, that most famous Scottish cloth. Let us turn then to the north.

Rob Roy, written in 1817 by Sir Walter Scott, is a historical tale of adventure set in the Scottish highlands with the mysterious and powerful Robert Roy MacGregor (Rob Roy) at its centre. The heroine of the novel is Diana Vernon, brought up to hunt, ride and fight as well as her male cousins. She eventually marries the story’s narrator, Frank Osbaldistone, but not before much intrigue is overcome and blood has been shed around the beautiful mountains and valleys of Loch Lomand.

The novel was turned into a play, with the role of Diana Vernon taken on by many actresses in the nineteenth century. Across theatres in Scotland, from Edinburgh to Glasgow, Aberdeen to Perth, Rob Roy was a hit. Such was the play’s popularity that in 1836, Corbett Ryder re-opened in Rob Roy for the 551st time! There was even a theatrical proverb for failing establishments: “When in doubt, play Rob Roy”.

There is no record of Louisa Nisbett playing Diana Vernon, but almost everyone did at some point. Some of the portraits we have of actresses in the role help us to rule them out, from their dates and dress. Catherine Stephens, later the Countess of Essex, was depicted from 1818-1820 in the role, but as we can see, not in the costume of our figures.

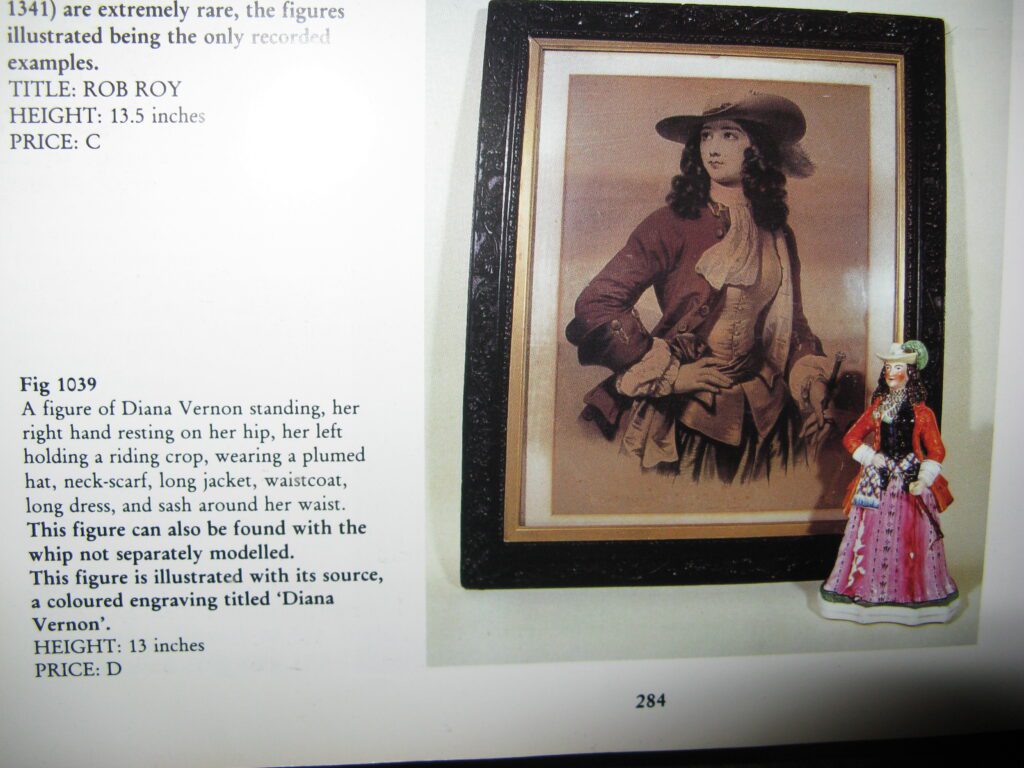

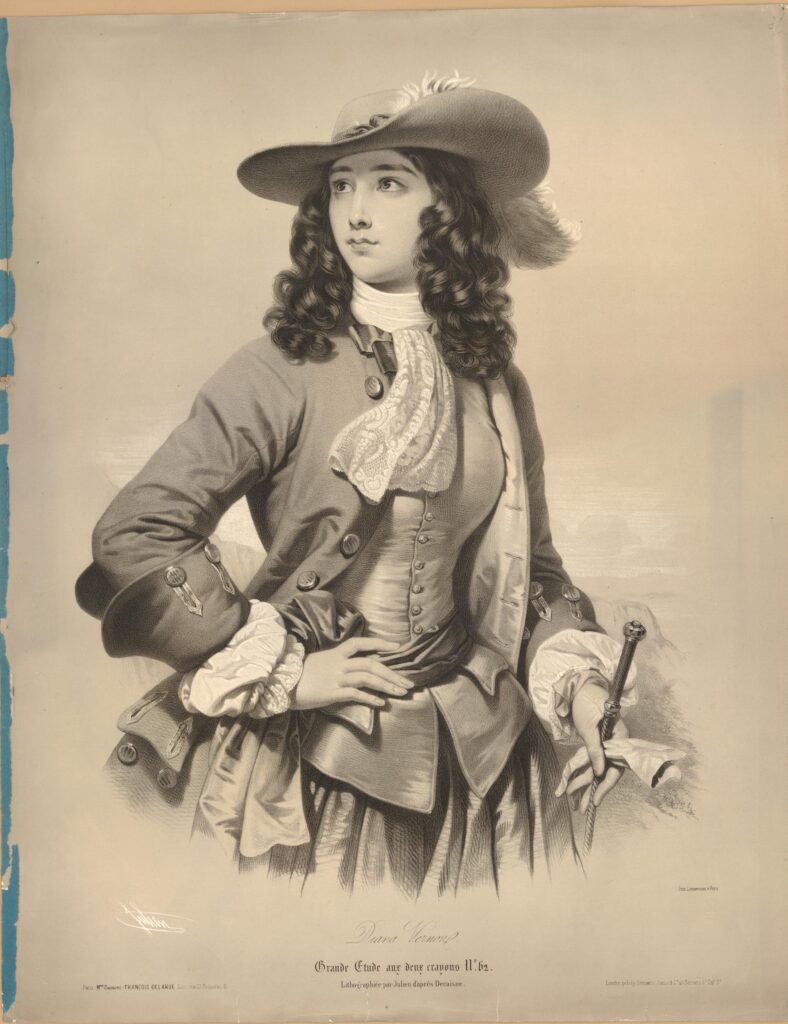

It seemed like another dead end, but consulting our Harding book, we find an image of Diana Vernon, which matches the pose of our figures almost exactly. According to The British Museum, this lithograph print of the Hon. Diana Newton dressed as Diana Vernon was published in London between 1850-1865, but the original painting (now lost) by Henri Decaisne must have been made before 1852, as Decaisne died that year. Diana Newton was not an actress; she was the wife of Charles E. Newton, and we can find very little information about either of them. It seems likely that the original painting was made in England, though Decaisne was Belgian. Perhaps the Newtons were attending a fancy-dress ball and this was Diana’s costume. Perhaps they had Scottish friends and were celebrating Burn’s Night on 25 January in style.

Further research revealed that another artist, Edouard Wayer, painted his own version of Decaisne’s Diana Vernon and made hundreds of copies for the opening of the Musée Barrois in France in 1849.

Finally we know both the character depicted and the individual model for our figures. Not Louisa Nisbett or Miss Elphinstone – not an actress at all, but an aristocratic lady in a costume from one of the most famous plays of the time, produced by the Alpha Factory c1848. What a journey we have been on, but the result was worth it. Our three figures of the Hon.Diana Newton as Diana Vernon from Rob Roy bring a little of the Scottish highlands to our Lancashire moors everyday, and we are grateful for that.

An earlier version of this piece was published in the Autumn 2022 Staffordshire Figure Association newsletter. Additional research by Sarah Gillett.

Dorothea Gillett and her husband Kelvin have been collecting Staffordshire figures for over 50 years, and previously ran an antiques shop in Chester, England. Their daughter Sarah is an artist and writer who draws from her own collection of curiosities and antiquities in her work.