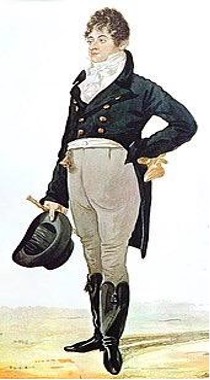

The pre-1830 dandies are some of our favourite Staffordshire figures. These figures depict young men and women in an elaborate, some would say ostentatious, style of dress. They were modelled in different sizes with and without bocage. One common feature is that most, if not all, have a male figure, a dandy, and a female companion called a dandizette. Most pairs of dandies and dandizettes were modelled on the same base, but not all.

A dandy, historically, is a man who places particular importance on his physical appearance, including refined and precise language, and leisurely pastimes associated with the upper class. A dandy was often a self-made man who attempted to imitate an aristocratic lifestyle despite coming from a middle-class background. The clothing they chose marked the true beginning of modern masculine dress. The modern practice of dandyism first appeared during the revolutionary 1790s, both in England and France.

The French Revolution had shaken the political and cultural foundations of Europe, including the transformation of men’s clothing during this period. French young men of the streets altered prevailing styles of dress not only for propaganda purposes, but also for creating an identity through their dress. At this point, France’s formerly unquestioned leadership in men’s dress began to be overshadowed by English influence. The English look, based on equestrian clothing and more form-fitting tailoring, appealed to young Frenchmen in the upper and middles classes. The adoption of county style boots rather than shoes for city wear also increased in popularity.

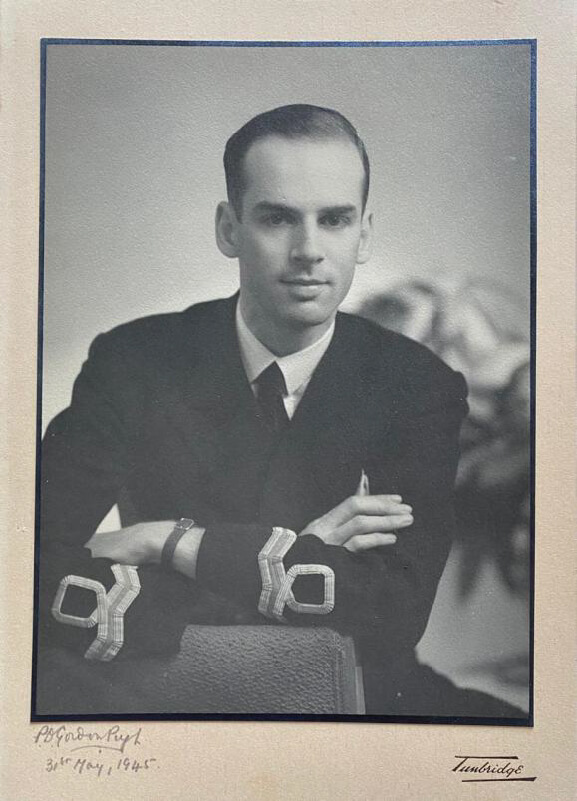

Male clothing was greatly influenced by the presence of a fashionable young Englishman, George Bryan “Beau” Brummell (1778- 1840), in London society in 1799. Beau Brummell in his early days was an undergraduate student at Oriel College, Oxford.

Brummell was not from an aristocratic family; indeed, as the literature states, his greatness was “based on nothing at all.” He was always powdered and perfumed, immaculately bathed and shaved, and wore all freshly laundered clothing. In his earlier years his plain dark blue coat was something of his trademark.

Caricature of Beau Brummell by Richard Dighton (1805)

Brummell led the transition from breeches (trousers reaching to or just below the knees) to snugly tailored dark “pantaloons,” which led directly to contemporary trousers, the mainstay of men’s clothes in the western world for the past two centuries. The trousers were often so form fitting that pockets were largely useless. This led to “dandy” men carrying a reticule (a purse).

Although Beau Brummell inherited a substantial sum from his father in 1799, he spent freely on clothes, high living, and gambling. By 1816 he had to declare bankruptcy and shortly thereafter fled to France to avoid his creditors. He died penniless in 1840 in a French asylum.

Female dandies, or later termed “dandizettes,” overlapped with male dandies for a brief period during the early 19th century. Dandizettes was a term applied to feminine devotees to dress and their absurdities were fully equal to those of the dandy. They wore strikingly large hats and bonnets, and for the first time, their dresses were raised to reveal their ankles and, as we would say in today’s vernacular, a bit of leg. These fashionable ladies always wore gloves when going out of doors and also carried a reticule. For all the eccentricities of Beau Brummell and his adherents, we now have wonderful visual evidence of the dandy movement through many lovely Staffordshire figures which grace our homes. Beau would be proud!

top row – on left 8.5″ high; on right with bocage 8″ high;

bottom row – two lovely pairs of dandies with interesting bocage, each 7.2″ high

Win and Pat Hock live in Boalsburg, central Pennsylvania. Win is a retired professor of plant pathology from Penn State University, Pat is a quilter and loves cooking, and both are avid gardeners. They collect figures from 1780-1840, Victorian dogs and other objects including a collection of pastille burners. The figures in this article are from their collection.

This article was first published in the Summer 2019 Staffordshire Figure Association members’ newsletter. Join us today to receive more articles written by experts and be part of our knowledgeable community.